The slowest foods on the planet are worth the wait

Slowly does it

Kimchi: one to 20 days

Kimchi: one to 20 days

The fermentation time varies depending on temperature (it ripens more quickly if it’s warm) and personal taste, with most home kimchi makers resting their jars anywhere from a couple of days to a couple of weeks. Traditionally, kimchi is made in the winter, when it benefits from a long and slow ferment. The low temperatures keep vegetables like cabbage and radish crispy, with a deeply funky fermented flavour.

Sponsored Content

Fermented dill pickles: one week

Kombucha: one to six weeks

Kombucha is a sweet and tangy fermented tea that can be purchased commercially or made at home. Making kombucha starts with a slimy mass called a scoby (an acronym for symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast) that makes all of that magical fermentation happen. The longer it brews, the bolder the flavour – and the fizzier the bubbles. First-time home brewers should add another week or two onto the production time if making a scoby from scratch.

Sauerkraut: two to four weeks

Sponsored Content

Dry-aged beef: 15 to 100 days

Dry-aged beef: 15 to 100 days

Salami: four to 12 weeks

Sponsored Content

Preserved lemon: one month

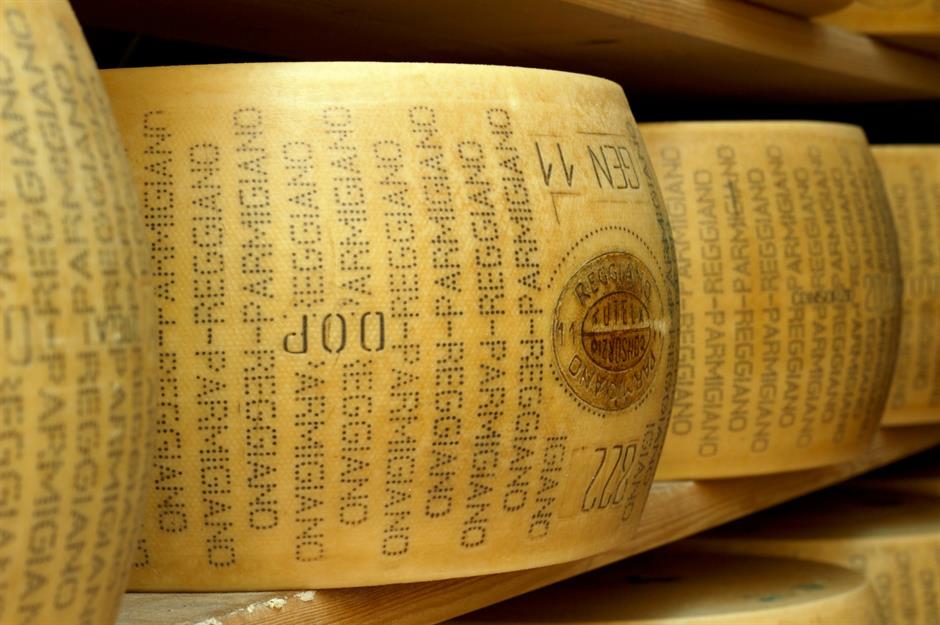

Cheese: one month to 10+ years

Cheese: one month to 10+ years

Once cheese has aged for a year or more, you start to get real changes in flavour and texture. Parmigiano-Reggiano only forms its signature grainy texture after it has aged for at least two years. Gouda that’s aged for five years develops crystals of calcium lactate, which give the cheese extra tang and a strangely alluring crunch. Cheddar is a cheese that seems to benefit from almost endless aging – 10 or 15 years is hardly unheard of.

Sponsored Content

Fruitcake: six weeks to five years

Love it or hate it, fruitcake is a tradition in many families, especially around the festive season. Some fruitcakes can be eaten immediately after baking, but most purists swear by aging their cakes, either for a few weeks or for a number of years. As a cake ages, the dried fruit releases tannins to deepen the flavour. Over time, alcohol is added to 'feed' the cake and keep it moist. The longer it ages, the more chance it has to absorb that brandy, whisky or rum.

Century egg: three months

Gochujang: four to six months

Sponsored Content

Soy sauce: five to eight months

Miso: six months to two years

Miso is a salty fermented soy bean paste that's used as a base for soups, and to flavour dressings, marinades and glazes. It's graded by colour, and that colour is determined by how long the paste is left to ferment. White or yellow miso paste is the most common and likely what you’ll find in your sushi combo soup, whereas red or more heavily aged miso has a more aggressive flavour.

Sake: seven months to three years

Sponsored Content

Prosciutto: nine months to three years

Vanilla extract: 12 to 14 months

Wine: one to 20 years

Sponsored Content

Jamón Ibérico: two to four years

To the untrained eye, Jamón Ibérico, a cured ham from Spain, may look like prosciutto – but the two are different for a number of reasons, including price (Jamón Ibérico is one of the most expensive meats in the world). The ham is sourced solely from the legs of rare black Iberian pigs that feast on a diet of acorns. The legs are packed in salt for a few weeks, then left to cure for anywhere between two to four years. As the ham cures, the fat breaks down and becomes melt-in-the-mouth tender.

Tabasco: three to five years

Whisky: three to 50 years

Sponsored Content

Whisky: three to 50 years

Aged tea: five to 40 years

Balsamic vinegar: 12+ years

Not all vinegars with the word 'balsamic' on the bottle are created equally. Many of the cheaper supermarket brands are simply regular vinegars made to mimic traditional balsamic vinegar from Modena, Italy. The proper stuff is rich and syrupy, thanks to a barrelling process that involves the vinegar being moved through a series of increasingly smaller barrels over the course of at least 12 years, allowing the moisture content to slowly reduce.

Sponsored Content

Balsamic vinegar: 12+ years

Traditional balsamic is often barrelled for up to 25 years. It can be identified by the words Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale on the label, a Protected Designation of Origin stamp and a fairly hefty price tag. Unlike the faux grocery store brands, it should never be wasted in a salad dressing or as a cooking ingredient. Use it sparingly as a condiment over everything from grilled meat to fresh berries.

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature